Jacob Braun

On December 26th, 1991, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics was dissolved into its 15 constituents— signifying the end of the Cold War. The capitalist western powers were finally able to reach through the Iron Curtain and begin the arduous process of democratization within states formerly subjugated by the Warsaw Pact, marking an era of increased European political and economic interconnectedness. However in the liberalization process of states such as the former East Germany, Poland and Hungary, the USSR had left behind the perfect storm of conditions for today’s populist parties to emerge; steeped in anti-establishment, anti-elitist and ultra-traditionalist rhetoric. The democratization experiment was something unfamiliar to most, and certainly had the possibility for improvement following the western powers’ first attempts in the aftermath of the Second World War. In my opinion though, we’ve gravely mishandled this situation which has allowed for the growth of a dangerous “populist plague.” If not properly amended, the inevitable takeover of Europe by right-wing populist parties will have dire consequences.

Life behind the Iron Curtain was very harshly regimented. One’s loyalty to their local communist party was of utmost importance to the authorities, lest they allow capitalist dissidents to run amok. Essentially, from 1946 to 1991 a herculean campaign of repression was undertaken across eastern Europe to foster the collectivization of society. After the dissolution of the USSR however, all of this oppressive architecture would vanish— finally allowing for these states’ transitions to democracy to occur. Initially, cooperation between western institutions and former communist states went smoothly. As time went on though, the groups most repressed by the USSR became more agitated and active in national politics; seeing organizations like the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the European Union (EU) as no more than mimics of their former Soviet overlords. An odd combination of nostalgia for the Soviet period and hatred for its communist governance combined to propel groups like the Alternative for Germany (AfD), Fidesz and the Law and Justice Party into the forefront of European politics.

East Germany was perhaps one of the more repressive states to have existed during the Cold War. So, how has a party rooted in authoritarian conservatism been able to rise to prominence? Under the auspices of the Soviet Union and the watchful eyes of the Stasi (East Germany’s secret police, one of the most effective in history), the East German identity was shifted away from the individual and instead towards the community. The state was to be the most important organ in everyone’s lives— and individuals were solely cogs in the machine of the advancement of socialism. Post-reunification, many young Germans born in the territories of the former East Germany felt they had no identity to rely on[1]; a major factor for AfD politicians to take advantage of. If populism can offer a solution for problems caused by the former East Germany, prospective voters are more than willing to overlook its racist and xenophobic leanings.

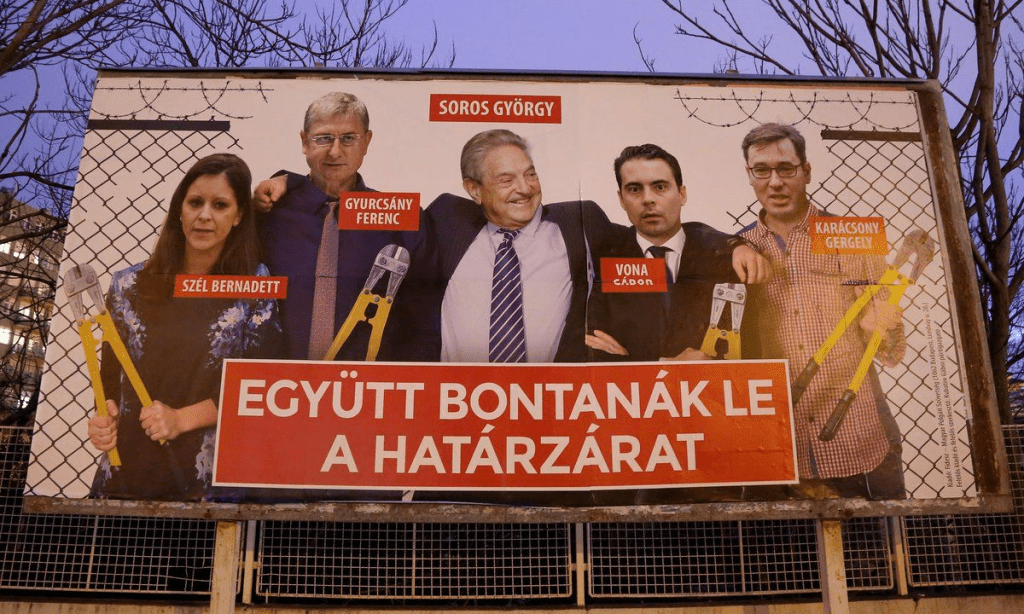

The Fidesz Party of Hungary adopted a similar strategy to that of the AfD— filling a void for voters with the promise of problem solving through direct democracy, as well as attacking democratic European institutions interpreted as detrimental to Hungary’s future[2]. Hungary too was subjugated under the Iron Curtain and was even invaded by its former Warsaw Pact allies in 1956[3], which would understandably cause many Hungarians to be weary of supranational institutions. Although a light amount of skepticism can be healthy, the skepticism promoted by Viktor Orban is rooted in antisemitism[4] and strongman authoritarianism that seeks to destroy the EU from the inside. Coincidentally, Orban is a close ally to Vladimir Putin.

While AfD and Fidesz take advantage of the nostalgic aspects of populism, the Polish Law and Justice Party associates more with its religious aspects. Under Soviet State Atheism, Poland’s majority Christian population was severely repressed. Following the dissolution of the USSR however, this bottled-up religiosity was allowed to run wild; entrenching itself among far-right politicians and used as a tool to demonize the decadent west. Poland’s Law and Justice Party seek a return to Christian tradition and to do away with western degeneracy, such as abortions (which they have banned outright since 2021)[5] and homosexuality (which has been banned in entire regions of the country since 2019)[6].

It is apparent that populist parties have their roots in the totalitarianism of the former communist sphere. The USSR laid the foundations for today’s turbulent political climate, which has been exploited by its successor state, Russia, as a means to destabilize the west. This is an issue which must be recognized— if we do not prescribe the accurate antidote for the plague of populism, we will certainly lose this second Cold War we find ourselves in.

Sources:

Why young eastern German voters support the far-right AfD – Deutsche Welle

The Secrets to Viktor Orban’s Success – Foreign Policy

Remembering the 1956 Hungarian Uprising – Radio Free Europe

Viktor Orban’s anti-Semitism problem – Politico

How woman are resisting Poland’s abortion ban – Aljazeera

Polish Court Rejects Case Against ‘LGBT-Free Zones’ Activist – Human Rights Watch

Reblogged this on The Plague of Populism.